Erin Goodling takes us to Portland and helps us think through how a situated urban political ecology approach can help theorize the dialectic of revanchism and resistance in a so called “sustainable city”. And in this post, Neil Smith is meeting AbdouMaliq Simone and Edgar Pieterse!

In multiple venues, situated urban political ecology (SUPE) organizers Henrik Ernstson, Mary Lawhon, Jonathan Silver, and colleagues build on Ananya Roy (2009) (and others’) claim that urban theory can and should emanate from the Global South. The authors address the question of how new theories generated in/from/of the Global South might be enacted, pushing back against the trend of forcing Northern-generated theory into a Southern context. Specifically, they ask how urban political ecology approaches can be expanded to account for not only a broader set of cities (Lawhon, Ernstson, Silver 2014), but – especially pertinent to my own research – also a broader array of people and practices in these multiple urban contexts.

This Portland mural depicts one imaginary of what the so-called sustainable city can and does look like (for some). Artist: Sara Stout. Source: Author.

I take inspiration from this question in thinking about how my very nascent dissertation research in Portland, Oregon (U.S.) might also draw on and generate contributions toward a situated urban political ecology. Portland is a city that not only sits squarely in the bowels of Western planning rationale (Watson, 2003), but that generates and exports much of the Western planning tradition’s accepted practices and assumptions around ‘sustainability’ planning. This transmission happens through institutions such as First Stop Portland, which invites delegations from as far as Kenya, Thailand, Japan, Colombia, and China to interact with Portland business leaders, professors, planners, and City officials in an effort to spread Portland’s sustainability acumen far and wide.

Portland is therefore an easy city to critique. Not surprisingly, paradoxes hide in the walls of LEED-certified buildings, and hypocrisies lap at the banks of the Willamette River every time a hard rain comes through and the sewer system overflows. One of the most profound contradictions in Portland is around ‘environmental gentrification’ (Checker, 2011): as low-income community groups make environmental improvements, property values rise and the cultural character of the area changes, and those lacking purchasing power are pushed out.

Although various stories of sustainability’s contradictions remain incredibly important to trace out, merely describing the ways that the sustainable city becomes completely inhospitable and unaffordable to low-income households and communities of color lacks the teeth needed to disrupt its oppressive operations.

I see a situated urban political ecology that is as attuned to structural critique as it is to everyday practices, such as drinking water, growing food, and sleeping, as one lens through which to better understand how transformative change might come about at different levels and scales.

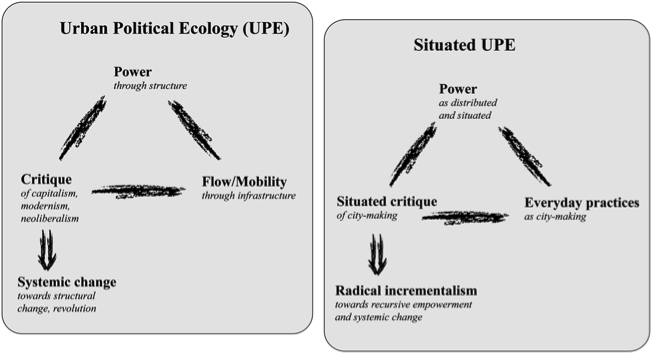

I build on Lawhon, Ernstson and Silver’s (2014) thinking about how “everyday practices as city-making”, “power as situated and distributed”, and a “situated critique of city-making” yields a theory of change that more readily embraces the notion of “radical incrementalism” (Pieterse, 2008) – rather than systemic change of a less concrete nature (see diagram below). This is a powerful and very relevant concept for not only the cities that Lawhon, Ernstson and Silver mention (e.g., Lagos, Cape Town), but also cities like Portland. But in making this assertion, I also take cues from James Ferguson (2012) to be weary of thinking in “hemispheric terms”; rather, Lawhon, Ernstson and Silver have inspired me to, again in Ferguson’s words, “[defamiliarize] habitual ways of thinking.”

‘A simplified overview of Urban Political Ecology as currently practiced (left side) and a situated UPE (right side).’ Source: Lawhon, Ernstson and Silver, 2014.

I currently work with two grassroots coalitions working to make socioenvironmental improvements that first and foremost benefit the groups’ marginalized constituents. The first group is a coalition of four neighborhood-based organizations carrying out a variety of community development initiatives – from workforce training to affordable housing development to culturally-specific education. Leaders have initiated a campaign to help current residents – largely low-income and people of color – stay in the neighborhood as property values and housing costs increase, and are currently working to build an organizing base.

The second group is a collective of community of color groups, Native American organizations, homeless activists, conservation organizations, and environmental justice organizations that are invested in the outcome of Portland’s Willamette River Superfund site cleanup. The collective aims to ensure that remediation will benefit those that currently use the waterway for subsistence fishing, as a home (either on small boats or along its banks), and for historical and present-day spiritual and recreational purposes. As the river receives more attention from the City and developers eyeing its banks as future condominium sites, police clearances of those camping along the banks of the river or sleeping in boats converted to homes have ramped up. Members of this collective are evolving their thinking about how to resist these sweeps, as well as more widespread displacement that may come down the line as the river becomes less toxic.

As I mentioned, I am only in the very beginning stages of this research. But anecdotes so far lead me to hypothesize that several threads that SUPE organizers are thinking through are useful in theorizing how transformative change might happen in Northern cities of relative affluence – with serious racialized and spatialized disparities – such as Portland.

First, Lawhon, Ernstson and Silver draw on Simone’s (2004) notion of “people as infrastructure” to argue that material relations in cities of the Global South are less stable and universal than assumed by (Northern) urbanists; rather people provide the networks. There is therefore less of an imperative to pay attention to hard infrastructure as in classic urban political ecology treatises, because pipes and roads are only partially responsible for how cities actually work. While this angle might give some clues for what is happening in cities such as Portland, the urban poor makes up an (increasingly) smaller fraction of the population and therefore accounts for proportionally fewer of the overall material flow vectors in this particular city.

But for the two areas of Portland where I am working, infrastructure looks much different than in the vast majority of the city; people, indeed, make up much of the networks that make these particular places ‘livable’. Moreover, coalition leaders discuss how crucial such people-centered networks will be for resisting displacement in due time. So, although the everyday practice portion of Lawhon, Ernstson and Silvers’s (2014) thinking does not necessarily help us explain how Portland currently works on a large scale, it can nevertheless help understand how it works in small pockets, and how it could work more broadly – that is, it helps establish a theory of socioecological change that is situated in a particular place, while remaining conscious of broader structures and trends.

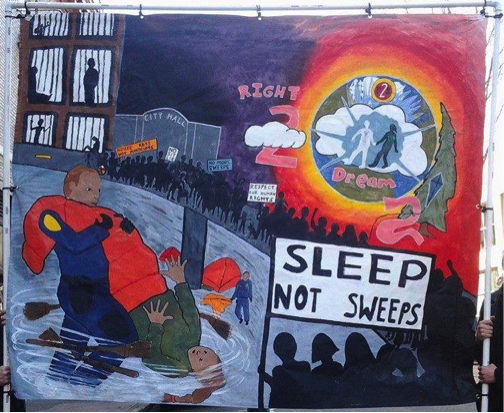

Everyday practice is the second SUPE theme relevant to my work, particularly in how the two coalitions described above ascribe political meaning to everyday actions. The first group is organizing around access to childcare, green space, and housing as key concerns around which to build a base of support. The second has explicitly articulated resting as a radical act, as a means of organizing and fighting for a right to central city space at municipal budget hearings and beyond.

I do not mean to romanticize elemental necessities of human life, nor to fall into a “trap of essentialism in reverse” (Bayat, 2010), attributing undue importance to ordinary behaviors. But it is nevertheless notable that everyday practices remain at the heart of the organizing strategies for these two groups.

A poster made by Portland activists, asserting their right to sleep and dream. Source: R2DToo Facebook page.

Finally, Edgar Pieterse’s (2008) notion of “radical incrementalism” very much seems applicable in these two cases. Building on Pieterse (2008), Henrik Ernstson (2013: 2; and in review) explains that:

[Radical incrementalist acts are those] by which residents, citizen associations and popular movements of the marginalized and poor choose to engage the state on a project-by-project basis to achieve incremental institutional changes to achieve a longer-term progressive transformation of the state. This field of antagonism and collaboration is not merely an arena of ‘service delivery’ and redistribution of material resources, but a shift in competencies and re-coding of the city administration. (Henrik Ernstson, 2013: 2; in review)

One change (among many) that hints at radical incrementalism for collective members of the group working on the Willamette River cleanup involves a resting station that several unhoused individuals set up on a vacant lot in a prominent section of downtown Portland. For three years, developers, neighborhood associations, and city council members have fought tooth and nail to have the ‘dreamers’, as they call themselves, removed. This group has essentially forced City leaders to acknowledge that their model of self-run service delivery works for far more houseless individuals than the shelters set up by social service agencies, and a nearby municipality has contracted with the resting station’s leaders to help them set up something similar.

I am excited to continue thinking through how a situated urban political ecology approach can help theorize in a more coherent whole the dialectic of revanchism and resistance in/of the ostensible sustainable city, especially as some pollination between the two coalitions I discuss here unfolds.

I am open to suggestions, comments, questions, critiques, and collaborations as this work evolves! Please don’t hesitate to get in touch at erin.goodling@pdx.edu. I thank Henrik Ernstson for helping to catalyze this thinking in a workshop we put together in Portland in April, and I look forward to many future SUPE interactions.

Works Cited

Bayat, Asef, 2010. Life as Politics: How Ordinary People Change the Middle East. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Checker, M. 2011. Wiped out by the ‘greenwave’: Environmental gentrification and the paradoxical politics of urban sustainability. City & Society, 23 (2), 210—229.

Ernstson, Henrik, 2013. Situating ecologies and re-distributing expertise: The material semiotics of people and plants at Bottom Road, Cape Town. [working paper, submitted to IJURR on 12 August 2014]

Ferguson, James, 2012. Theory from the Comaroffs, or how did you know the world up, down, backwards and forwards. Fieldsights – Theorizing the Contemporary, Cultural Anthropology Online, February 25, 2012.

Lawhon, Mary, Henrik Ernstson, and Jonathan Silver, 2014. Provincializing urban political ecology: Towards a situated UPE through African urbanism. Antipode, 46(2): 497—516. [Open Access.][Video Abstract, 3 minutes.]

Pieterse, Edgar, 2008. City Futures: Confronting the Crisis of Urban Development. London: Zed Books.

Roy, Ananya., 2009. The 21st-century metropolis: New geographies of theory. Regional Studies, 43 (6), 819-830.

Simone, AbdouMaliq., 2004. People as infrastructure: Intersecting fragments in Johannesburg. Public Culture, 16 (3), 407-429.

Smith, Neil, 1996. The New Urban Frontier: Gentrification and the Revanchist City. London: Routledge.

Watson, Vanessa., 2003. Conflicting rationalities: Implications for planning theory and ethics. Planning Theory & Practice, 4 (4), 395-407.