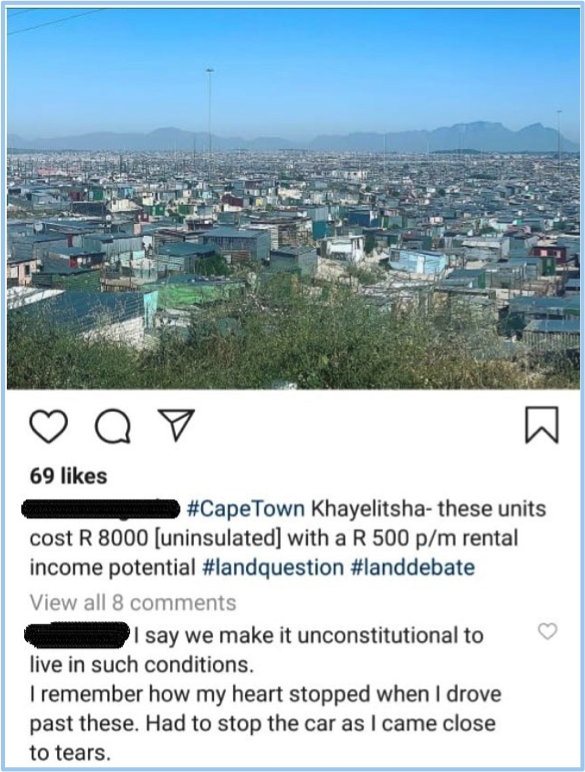

A recent Tweet [1] about the injustice of the rental housing stock in Khayelitsha, Cape Town, had me revisit my understanding of South Africa’s housing conundrum. My early career passion on urban slums and city spatial planning threw me into the abyss of just how difficult it is to provide dignified housing for all. Without major overhaul of the world economy, alongside systematic global redistribution of wealth, achieving spatial justice has proven a mammoth task. To be sure, the Bill of Rights of the South African Constitution (1996) states: ‘everyone has the right to have access to adequate housing’. While this leaves enough room for interpreting what ‘adequate’ is, there is a general public consensus in South Africa that living in a shack is not it.

As I will show in this piece, creating an informal settlement or putting up one’s shack is part of the on-going struggle for adequate housing and property rights in South Africa. Many have heeded the call by Lefebvre (1996[1968]) and argued that the ‘right to the city’ is the access to social freedoms required to achieve spatial justice (Dikeç, 2002; Mitchell, 2003; Harvey, 2008; Huchzermeyer, 2014). Few have discussed the particular and paradoxical conditions of spatial justice that query the universal understanding of what justice is for whom. Furthermore, few have questioned whether housing and property rights prescribed in the South African Constitution (1996) can achieve spatial justice in a relational and multiscalar way, from city to household level. My assertion here is that we have to be more careful not to synonymize the codification of legal rights with justice in order to see actually existing tensions of spatial justice.

In the South African National Housing Code (2009) the government explains what it means by ‘adequate housing’ and ‘sustainable residential environments’. Legally, it addresses these rights in a scalar and relational way. Originally provided in section 1 (vi) of the Housing Act, 1997 (Act No. 107 of 1997), it states:

the establishment and maintenance of habitable, stable and sustainable public and private residential environments to ensure viable households and communities in areas allowing convenient access to economic opportunities, and to health, educational and social amenities in which all citizens and permanent residents of the Republic will, on a progressive basis, have access to:

(a) permanent residential structures with secure tenure, ensuring internal an

external privacy and providing adequate protection against the elements; and

(b) potable water, adequate sanitary facilities and domestic energy supply.

An uninsulated living unit located in townships and neighbouring informal settlements in South Africa are generally made of corrugated iron, wood or plastic boards, or any other scrap materials. Colloquially they are called stand-alone shacks if they are part of a group of single shacks in an informal settlement (i.e. slum or ‘squatter camp’); or backyard shacks if they are set up behind a state-subsidised house built from bricks and mortar. Shacks have no direct access to water, power or sanitation. Shacks or ‘informal units’ have long been part of the South African urban landscape as a means for the poor to live closer to work and have easier access to the city. During Apartheid, creating informal settlements was a way for black women to live closer to their black male partners entering the city as migrant labourers, or to find their own informal jobs such as domestic work (Makhulu, 2015). The migrant labour system separated black families. In some ways, informal settlements were a political act to defy influx laws against black, rural migrants moving to ‘whites-only’ cities (ibid.). In the post-Apartheid era it has become a way to be counted, as I explain next

If you are a South African permanent resident, married or with dependents, and earning below R3500 (which increases slowly with inflation) you are eligible for a fully-subsidised house on a titled piece of land from the government. The National Housing Code (2009) provides a range of housing subsidy programs that municipalities can apply to on behalf of individuals and whole communities in need of housing. The Individual Subsidy Programme has been most prominent in the proliferation of what are commonly known as ‘RDP houses’ (Reconstruction and Development Programme) in old, new and expanding township areas. However, in the past decade, a shift has been made to include incremental upgrading in the housing process, toward eventual permanent structures on titled land. Like many rapidly urbanising countries experiencing high population growth and an inability to meet state-regulated housing demand, the shift away from slum eradication to slum upgrading was led globally by UN-Habitat. This was paramount in blurring the lines between ‘unlawful occupation’ or ‘illegal squatting’ and ‘informal housing’. In South Africa, informal housing is usually a shack – considered undignified and unjust by the general public.

To echo the Bill of Rights in the South African Constitution (1996) ‘the state must take reasonable legislative and other measures, within its available resources, to achieve the progressive realisation of this right’ – to housing. After independence many countries of the global South used loans and financial aid to provide necessary urban infrastructure and flesh out the newly formed government bodies. Socio-economic development programs were initiated, with the assistance of ‘more developed’ countries in the global North, to meet universal human rights standards provided by the United Nations (UN). However, it became evident that, as the deadlines set by the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) came and went without achieving these universal rights, the UN needed a more incremental approach.

Incremental upgrading of informal housing works in favour of the progressive realisation of the right to adequate housing. It supports a rental market as a livelihood strategy for the poor and it does not condemn living informally as a way to achieve Lefebvre’s much revered ‘right to the city’ movement. The National Upgrading Support Programme (NUSP) and other financial mechanisms or agencies are in place to boost the rental property market in townships through incremental improvements on properties (South African Department of Human Settlements, accessed 22 October 2019). Organisations such as the Development Action Group and SDI (Slumdwellers International) South African Alliance, or companies like Melana Developments are working closely with RDP-house property owners, the state and financial support entities to incorporate informality into legal rights. After all, universal adequate housing as explained in government documents is a long-term goal of the state. If the progressive realisation of the right to adequate housing is within constitutional bounds, then so must be kind of uninsulated unit / shack / informal unit the Tweet shows is being advertised. However, is it just to be living in such conditions?

Poor households renting out their shack for supplemental income is a contentious issue from a justice perspective if we consider the multiscalar and relational aspects of spatial justice. The housing conundrum exists within the constraints of slow urban land reform and unaffordable housing construction costs along market rates and regulatory standards. The rental markets also exist within the constraints of unemployment rates at 29% for the last quarter of 2019 – and higher if the ‘expanded definition’ and underemployment are considered (Webster, 2019 and Beukes et al., 2017). In response to the comment on the Tweet above, while it is unjust to live in undignified housing it would also be unjust to make it unconstitutional to live in or rent out a shack. The state has not and/or cannot provide enough adequate housing for everyone (at least not immediately), nor are there enough wage-earning jobs for sufficient household income.

In the context of achieving ‘the right to the city’ where informal housing units and informal settlements are no longer condemned or eradicated, different forms of justice are at odds with each other. Clear tensions exist between the right to access sustainable urban environments and the right to access adequate housing for all when the provision of both are futuristic (i.e. progressive). In effect they create inequality. What does spatial justice mean in cities where the codification of legal rights carries with it extreme differences in the ability to materialise these rights? At present millions can access urban environments and housing but dignified and sustainable living is dependent on state progress – which has delays in the decades. The current tensions of spatial justice should shift our gaze beyond legal rights to a complex of rights – political, economic and social.

[1] I received a copy of this tweet without identifiers on 17 October 2019 via WhatsApp

References

Beukes, R., Fransman, T., Murozvi, S. and Yu, D., 2017. Underemployment in South Africa. Development Southern Africa, Vol. 34: 1, 33-55. DOI: 10.1080/0376835X.2016.1269634

Dikeç, M., 2002. Police, politics, and the right to the city. GeoJournal 58, 91–98.

Harvey, D., 2008. The right to the city. New Left Rev. 53, 23–40.

Huchzermeyer, M., 2014. Invoking Lefebvre’s ‘right to the city’ in South Africa today: A response to Walsh, City, 18:1, 41-49, DOI: 10.1080/13604813.2014.868166

Makhulu, A., 2015. Making Freedom: Apartheid, Squatter Politics, and the Struggle for Home. Durham: Duke University Press.

Mitchell, D., 2003. The Right to the City. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Ranchhod, V., 14 February 2019. Why is South Africa’s unemployment rate so high? GroundUp, accessed 22 October 2019. Weblink: https://www.groundup.org.za/article/why-south-africas-unemployment-rate-so-high/

Republic of South Africa. Housing Act, 1997 (Act No. 107 of 1997). Accessed 23 October 2019. Weblink: http://www.saflii.org/za/legis/num_act/ha1997107.pdf

Republic of South Africa, 2019. South African Government: Housing. Accessed 21 October 2019. Weblink: https://www.gov.za/about-sa/housing#NUSP

Republic of South Africa, 2009. The National Housing Code: Part 3 Technical and General Guidelines.

Republic of South Africa, 1996. The South African Constitution, Chapter 2: The Bill of Rights. Accessed 24 October 2019. Weblink: https://www.gov.za/documents/constitution/chapter-2-bill-rights#26

Webster, D., 2 August 2019. Unemployment is South Africa is worse than you think. New Frame, accessed 25 October 2019. Weblink: https://www.newframe.com/unemployment-in-south-africa-is-worse-than-you-think/

[1] I received a copy of this tweet without identifiers on 17 October 2019 via WhatsApp